Japanese baristas: training in Italy for a greater expertise

by Roberto Sala Barista. His bar, the Mary’s Bar in Costa Masnaga, in the North of Italy, was set up by his great-grandparents in 1928. He was brought up surrounded by machines, bags and cups. Fifteen years ago he started his job behind the counter: from 2001, he is a coffee taster and Espresso Italiano Specialist.In February 2007, he has been appointed to the board of the International Institute of Coffee Tasters. He is the first barista who has been appointed to such a role.

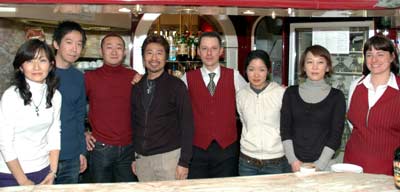

Recently, I hosted in my coffee shop some Japanese baristas who were accompanied by the infaillibly efficient Yumiko Momoi – the secretary general of the International Institute of Coffee Tasters for Japan. We spent a few hours together in my coffee shop. This was a great occasion for speaking about espresso and cappuccino and for working together at the espresso machine. Actually, Chihiro Yokoyama – a colleague who won several times the Japanese Barista Championship – was there with the group. First thought: all the baristas had an in-depth and specific knowledge of the entire coffee production process. Put it more clearly: they know what sort of processing the product they use every day went through. They’ve got clear views on the differences between the species, between the various ways of processing green beans and so on. This is not irrelevant: you can make the most of a semi-processed product such as coffee is only with a deep knowledge of how it is processed. This makes it possible to extract its specific sensory characteristics.

Recently, I hosted in my coffee shop some Japanese baristas who were accompanied by the infaillibly efficient Yumiko Momoi – the secretary general of the International Institute of Coffee Tasters for Japan. We spent a few hours together in my coffee shop. This was a great occasion for speaking about espresso and cappuccino and for working together at the espresso machine. Actually, Chihiro Yokoyama – a colleague who won several times the Japanese Barista Championship – was there with the group. First thought: all the baristas had an in-depth and specific knowledge of the entire coffee production process. Put it more clearly: they know what sort of processing the product they use every day went through. They’ve got clear views on the differences between the species, between the various ways of processing green beans and so on. This is not irrelevant: you can make the most of a semi-processed product such as coffee is only with a deep knowledge of how it is processed. This makes it possible to extract its specific sensory characteristics.

Second thought: strong preference for coffee with sharp acidity. The Japanese see a strong connection between this characteristic and the persistence of the espresso. They appreciate the blends from the North of Italy precisely because of their fresh acidity, nonetheless, they demand a highly delicate product. This is mainly due to a cultural reason: Japanese cuisine is a rampart of the delicacy of tastes and aromas. Adding to this point, confirmation of their preference for acid coffees came from the tasting of a pure Guatemala (for this occasion, I used the classic Italian moka because this is a delicate product which could have been ruined by the espresso machine). Anyhow, the Japanese baristas are well aware of the relevance of the blend: the single origins, despite their being interesting, are incomplete even from their point of view. This is an important common point of view with the Italian culture of espresso. Different views, instead, on cappuccino. Let’s say it: the Japanese, just like many foreign consumers adore it. There is, though, a difference between our cappuccino and theirs. The Italian traditional preparation method has no separate phase between the foamed milk and the coffee. The espresso must be blended with the foamed milk with the aim of obtaining a uniform cream. This characteristic, according to Yokoyama, is not fully appreciated by the Japanese consumer. This is the reason why the Japanese cappuccino is a mix of espresso and milk with a final top of foam which is often also decorated. This conveys to the beverage the typical note of tactile softness which comes from the milk foam on top. The point is that this creaminess does not characterise the overall cappuccino. This is a variation to the Italian recipe intended to better satisfy the preferences of the Japanese public. Given the professionalism of their baristas, the Japanese are a very lucky public.